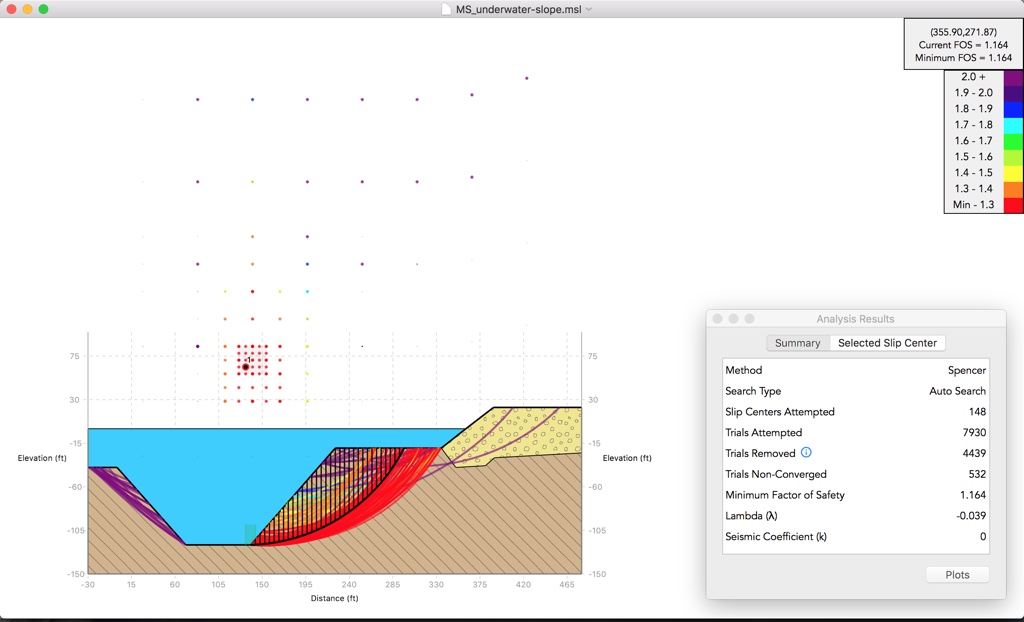

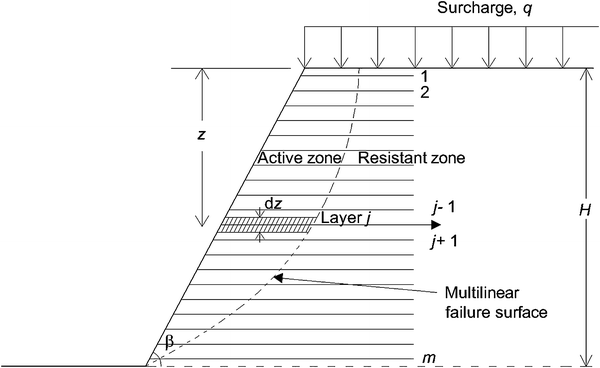

At the other extreme, slab-shaped slips on hillsides can remove a layer of soil from the top of the underlying bedrock. A 'shrinkage' crack (formed during prior dry weather) at the top of the slip may also fill with rain water, pushing the slip forward. This is combined with increased soil weight due to the added groundwater. Such slips often occur after a period of heavy rain, when the pore water pressure at the slip surface increases, reducing the effective normal stress and thus diminishing the restraining friction along the slip line. Nevertheless, failures in 'pure' clay can be quite close to circular. Real life failures in naturally deposited mixed soils are not necessarily circular, but prior to computers, it was far easier to analyse such a simplified geometry. Values of the global or local safety factors close to 1 (typically comprised between 1 and 1.3, depending on regulations) indicate marginally stable slopes that require attention, monitoring and/or an engineering intervention (slope stabilization) to increase the safety factor and reduce the probability of a slope movement. Similarly, a slope can be locally stable if a safety factor larger than 1 is computed along any potential sliding surface running through a limited portion of the slope (for instance only within its toe). The smallest value of the safety factor will be taken as representing the global stability condition of the slope.

A slope can be globally stable if the safety factor, computed along any potential sliding surface running from the top of the slope to its toe, is always larger than 1. The stability of a slope is essentially controlled by the ratio between the available shear strength and the acting shear stress, which can be expressed in terms of a safety factor if these quantities are integrated over a potential (or actual) sliding surface.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)